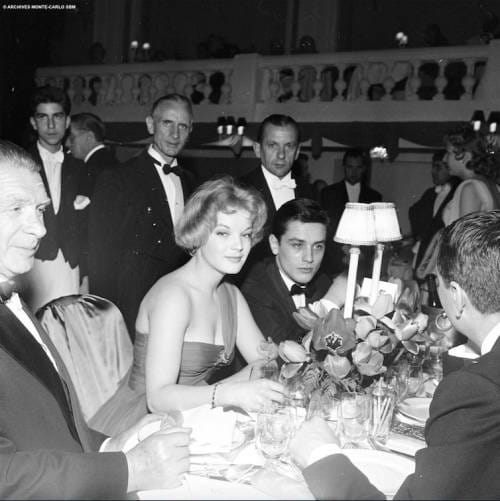

Anywhere in the Principality you will probably hear English, French, Russian, Italian, and possibly more languages spoken. Monaco is truly a multi-national playground and its residents are multi-lingual. However, the Monaco constitution of 1962 stipulates French as its only official language. But if you stroll through the narrow streets of le Rocher, you may hear yet another language that is strange to your ears. Munegascu, the native language of Monaco, considered a Ligurian dialect, is now only spoken by elderly Monegasques. For Generations, Munegascu was only passed on verbally and did not have an official Grammar system. But thanks to Louis Notari, it began to be taught in the Principality schools about 20 years ago. To introduce you to the life and work of the famous Monegasque, we met his grandson Frederic Notari and his great-granddaughter Charlotte Lubert-Notari who still live in the Principality.

In 1980, Monaco celebrated the 100th anniversary of Louis Notari’s birth with a major cultural event, presided over by Prince Rainier III and Princess Grace. The National Library and one of the Principality streets still bear his name. Why does the princely family and the Monegasque people pay so much tribute to this man? To answer this question, let’s go back to the late 19th century.

One of the oldest families in Monaco

On his mother’s side, Louis Notari, born in 1879, belonged to the Crovetto family, one of the oldest in Monaco. To this day, six generations of Notari have lived in the Principality. According to his grandson Frederic, the Notari family comes from Switzerland. Louis’ ancestors were Freemasons and settled down in Monaco following their duties. Among other things, Louis Notari’s father took part in the construction of Saint Nicholas Cathedral.

Once the Notaris set foot in Monaco, they never left. The family originally lived on Avenue des Citronniers, which today would be next door to the Metropol Hotel, but it has long since been demolished.

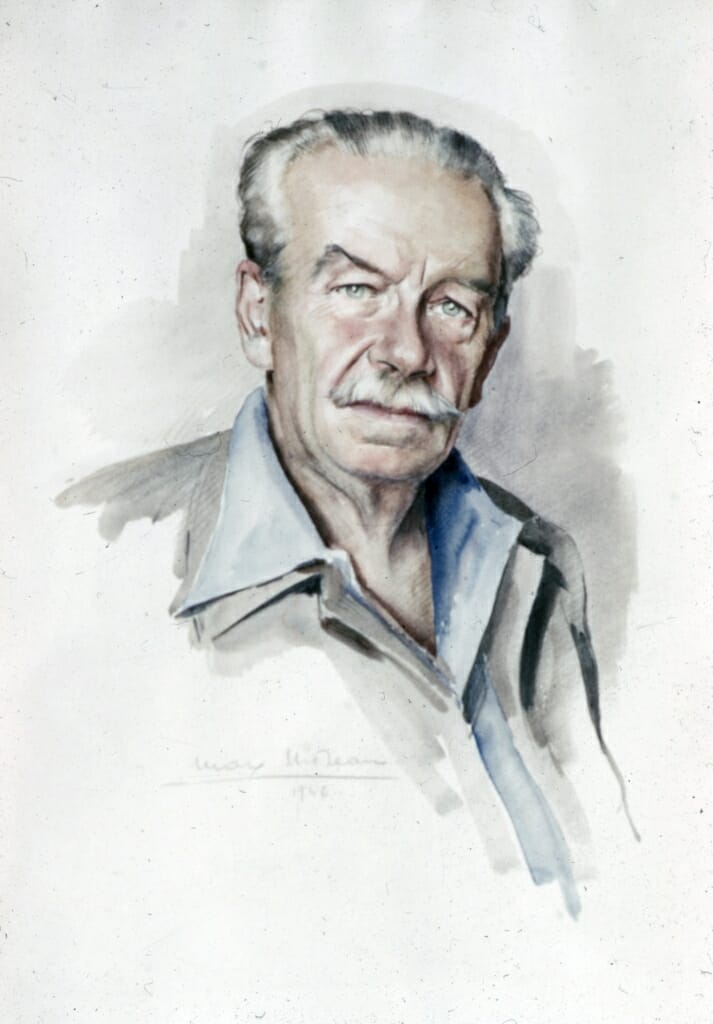

Louis Notari — an architect, politician and poet

Louis was one of three boys: Andre, a lawyer; Leon, a doctor; and Louis, who followed in the footsteps of his father. Once he finished his studies at College des Jesites de la Visitation (now the Lyceum of Albert I), he attended the Polytechnic School of Turin. After graduating as an engineer-architect, the young man furthered his career back in Monaco.

In 1911, Prince Albert I appointed Louis Notari as Head of Public Works (Direction des Travaux Publics), where he stayed until 1943. As an engineer and architect, Notari took part in the creation of the Princess Antoinette Park, opened in 1923 and still loved by all Monegasque children; and the Exotic Garden, opened in 1933, which became one of the most popular tourist attractions in the Principality. Notari also supervised the drilling of the Louis II tunnel.

Engineering, however, was only one of Louis Notari’s many passions. «He was a very open person», recalls his grandson Frederic, who used to spend his summer holidays with his grandfather. «The first things that come to my mind when I think about my grandfather are the village and nature. He loved fishing, mountains and hunting. We talked about plants a lot».

Louis Notari also played an important political role in Monaco as a member of the municipal council, and as state counselor from 1943 until his death.

Despite all of these accomplishments, it was in Monegasque literature that he became a pioneer. Notari was a talented poet and strived to develop the national Monegasque language, which was on the brink of extinction in the early 19th century. Louis Notari’s literary career started back in 1927. That’s when the Principality was seriously considering creating Monegasque grammar. During a Committee on Traditions’ meeting, Louis Notari mentioned the necessity of creating literary works in the national language, which Monaco had never seen published before. He was then invited to write a story about the patroness of the Principality, St. Devote. «The legend of Saint Devote», the first work in the native Monegasque language was written by Notari, earning him the nickname: «the father of Monegasque literature». He later wrote the lyrics to the Monaco national anthem and «U Campanin de San Niculau». This song is now part of Monegasque tradition and used to be a special song for Prince Rainier III, which was played during his funeral on April 15, 2005.

Notari penned three other books, including a collection of Monegasque tales «Bulughe Munegasche» and «Quelques notes sur les traditions de Monaco» (Notes on Monaco traditions).

Louis Notari’s Legacy

Notari’s works promoted the flourishing of native Monegasque literature. In 1960, Louis Frolla wrote a grammar manual for the Monegasque language. And other local authors, including Louis Barral, followed with their own published works.

At the end of his life, Notari was awarded the Order of St. Charles, the highest state award of the Principality of Monaco. In 1960, Prince Rainier III came to Notari to present the award, as the poet could no longer walk due to his old age.

Louis Notari died in Monaco in 1961. He left an important legacy and would be glad to know that today the Monegasque language is studied in Monaco public schools as part of the mandatory curriculum.