The fifteenth century saw many of the foundations put in place that would ensure Monaco’s survival over the next 500 years — not only survival, but most importantly, recognition as an independent country. Monaco has always been surrounded by large powerful states. In the fifteenth century Savoy, Anjou, Spain, France and regional centres of Italian power like Milan and Genoa were forces to be reckoned with. Monaco would be called upon to demonstrate military strength and diplomatic skill in equal measure to hold its own in the region.

Around 1447 Jean I of Monaco had created an important alliance with an old enemy Savoy to swing the balance of powers in the region in favour of Monaco. Savoy had previously laid siege to Monaco in an attempt to capture it for themselves but failed. This savvy move by Jean I to create a powerful protector in the neighbouring state of Savoy would be later undone by his son Catalan. In so doing Catalan created a power vacuum and unleashed forces that would test the next ruler of Monaco to the limit. Jean I’s formidable wife Pommeline Fregoso had played a critical role in repelling that earlier attack by the Duke of Savoy on the Rock. And it was at a particularly dangerous point in history for Monaco when the Duke of Savoy had managed to capture Jean I and hold him hostage. Pommeline’s tenacity would help preserve Monaco’s independence for Jean I, when fortune would have it, he was subsequently released from captivity. But ironically later in life Pommeline would prove a thorn in the side of Monaco and almost change the course of history again.

Jean I might have been clairvoyant when before his death he laid down the rules of succession of Monaco’s leaders in favour of male heirs. His only son Catalan, by his marriage to Pommeline, would become Seigneur of Monaco after him, but died three years into his reign leaving a very young daughter Claudine as head of the Monaco branch of the Grimaldi’s.

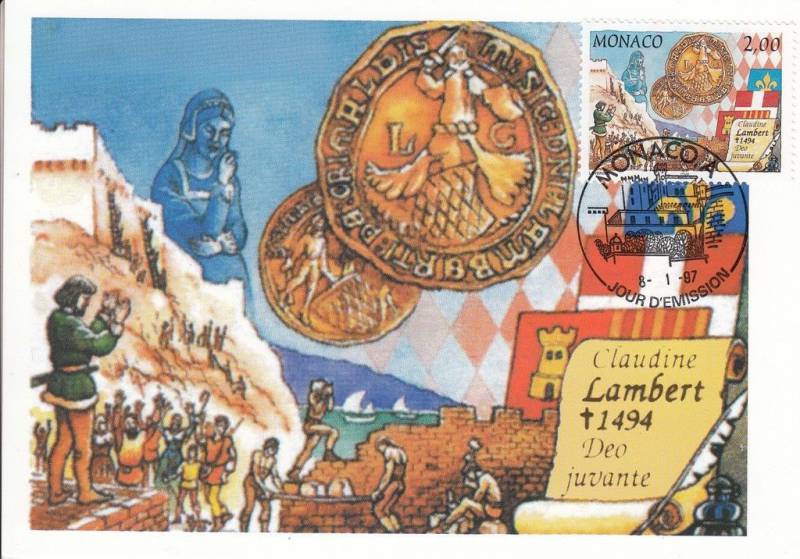

Following Jean I’s succession rules, a Grimaldi cousin, Lambert, from the ruling family in Antibes emerged as Claudine’s suitor while she was still a minor (from as early as age 6). According to Jean I’s rules, any female head of the family in line for the succession must marry a Grimaldi in order to maintain the Grimaldi leadership intact. Thus, everything was put in place to establish Lambert as the new ruler of Monaco. For Claudine to officially abdicate her powers, she had to wait until Lambert could marry her. Even before officially marrying Claudine when she would be fourteen years old in 1465, Lambert was recognized in 1458 as Seigneur of Monaco by King Rene of Anjou and Milan’s rulers (the Sforzas). It fell to Lambert early in his reign to deal with intrigue from Pommeline in addition to the consequences of his predecessor Catalan having ripped-up the treaty with Savoy.

There followed one of the most turbulent periods in Monaco’s history but with a leader then at the helm able to steer Monaco through every storm. The Rules of Succession created by Jean I had proven fortuitous as Lambert would show his mettle over the next thirty-seven years.

Born in 1420, Lambert would need all his experience and wisdom attained by the age of forty-five when he married Claudine. And his first tests would be a series of military assaults and rebellions in Menton and Roquebrune which were eventually put down. He also succeeded in defeating a subsequent attack by his own cousin Lascaris.

Lambert built a reputation for composure and cool-headed strategic calculation in the face of repeated crises. His many talents overflowed into business. His frugality meant that he was able to finance the rebuilding of Monaco’s own fleet which he kept in a constant state of readiness. And he was able to pay for a garrison of 400 soldiers to be stationed on the Rock.

Ironically, for all the military victories, Lambert’s weapon of choice was diplomacy. If ever there was a disciple of the adage «the pen is mightier than the sword» it was Lambert. He astutely turned to France, dispatching his brother Jean-André the Bishop of Grasse to negotiate with the court of Louis XI. Lambert was strategic and patient. Unsuccessful initially in these negotiations with the French King Louis, his next move on the diplomatic chess-board was to marry his son Jean to Antoinette of Savoy. This match was looked upon favourably by the French so when King Louis was succeeded by King Charles VIII, Lambert closed the deal he had patiently sought.

But what a deal — protection without surrendering independence! The documents signed in 1489 clearly leave out total submission to the French King as liege lord. And critically the French had no rights or authority over Monaco. In addition, Lambert became Counsellor and Chamberlain to the King of France. This was the crowning achievement of Lambert’s 37-year reign — independence and protection for Monaco. With France’s protection assured, he was able to rid himself of any intrusion by hostile Italian feudal rulers such as the Duke of Milan and the Doges of Genoa.

As if Lambert’s military and diplomatic successes were not enough, he also left a full Treasury. And he had one additional legacy to bequeath on Monaco’s ruling families that would endure; he created an official motto to guide them. And it reflected a modesty flowing from sincere religious beliefs. Over 500 years later Monaco’s official motto of the House of Grimaldi is Deo Juvante — «With God’s help». Lambert died in 1494 having created a family of six children with Claudine. Jean II, his son, would succeed him to take Monaco into the sixteenth century.